I am teaching again! Now online, making a virtual pilgrimage to the Black Madonna that ends up in Love Cemetery.

https://theshiftnetwork.com/course/01CGalland01_21

Best,

China

I am teaching again! Now online, making a virtual pilgrimage to the Black Madonna that ends up in Love Cemetery.

https://theshiftnetwork.com/course/01CGalland01_21

Best,

China

Resurrecting LOve: Dispatches from the Front:

Love isn’t only a cemetery or a documentary film I’ve almost finished or a book I published or my feelings for my children.

Can I love Donald Trump?

Love means I have to fill in the blank with the name of anyone I might think of as “my enemy.” I have to learn to love them too.

I hear that Sufis say that “the worst is the best.” Whether Sufis say that or not, Buddhists and Christians talk about it too, learning to love our enemies. Yes, even someone who seems like an impossible liar. What? Even free-form American 12-step programs say that we have to purify our hearts of anger or resentment, no matter how justified. That doesn’t mean that all is forgotten, that no injury occurred. It does mean that my intention needs to be that I’m open to compassion, even though I might fail to have it intially. It means that I can pick myself up and keep moving in the direction of loving kindness, I can keep moving in the direction of compassion.

My preference is to write someone off, ignore them. Not judging the person doesn’t mean giving up good judgment, or analyzing behaviour. It does mean not nursing negative feelings, not assuming that so and so is the incarnation of evil itself. Of course it’s more colorful and terrifying to imagine an other as without redeeming merit, a danger to all. I always loved being scared out of my wits – riding the roller coaster, diving off the cliff, you name it, whatever was forbidden, the question was could I get away with it? No.

Love is actually a choice, a direction I can move in, a breath that offers a moment of recollection, and a question:

What is my motivation? Am I in love or am I in fear? The honesty with which you or I or anyone answers this question determines one’s fate. Be honest.

Justified anger is easy and seductive. “But, but they, THEY…” we sputter. The most useful spiritual advice I’ve received to date is be willing to be 100% responsible for myself/for yourself. Emotions – whatever they are, anger or ectasy, they’re mine, they’re yours. The poet John Donne was correct, we are not islands, however, I haven’t been able to change anything that I’m not willing to be responsible for.

If I claim that YOU, whomever “you” might be, caused my anger, created my upset, whatever it is that makes me uncomfortable, then I just gave away my chance to change. I gave my power to you.

In this time of uncertainty and heightened emotions, whether from the upcoming holidays, the joyous occasion of a healthy child’s birth, or the elections, the loss of a job, or the death of a loved one, it can be hard to find that moment to breathe. I’m off on the roller coaster of emotion that even a headline – true or false – can set off.

Breath is the antidote. Followed by another breath. In silence. The putting aside of the world’s siren call of seduction. Whether it’s three minutes locked in a bathroom stall in a work place or in my own room 30 minutes before I have to leave, I can choose to be quiet, I can put a buffer between myself and the stories that activate my life.

“Darkness is invisible light” is a phrase I came up with many years ago while researching dark or black matter in science. I’m not a scientist so this was a lay person’s attempt to grasp a concept that even science cannot measure. In some ways, even calling “it” dark or black matter is filler for the lack of being able to know what “it” is – that main stuff of which the universe is composed. Percentages vary over the years, but the bottom line remains: most of what the universe is composed of is dark to us, beyond what the human eye can see.

I consulted an astophysicist at U.C. Berkeley as part of my research on the Black Madonnas years ago. Black or Dark Madonnas are a mainstream European Christian Catholic tradition that white America has generally ignored in its eagerness to import “valuables” from Europe.

I asked him whether or not my phrase, “ Darkness is invisible light,” was scientifically accurate. He said that it wasn’t scientifically accurate in terms of how astrophysics would describe dark or black matter, still, he said it was roughly accurate, it was correct in a poet sense. I’ve used it ever since.

As the darkness deepens this time of year, I find it especially useful to reflect upon the scientific reality that occassioned my poetic shorthand – we live in the dark. We think we “see” but in fact our eyes can only perceive a certain spectrum of light and that spectrum is only 5-7% of what the universe is made up of. We can pick up the gravitational effect of dark or black matter, but we can’t get our instruments or our minds around “invisible light.”

The illuminated spectrum we see, we navigate by, what we describe as “real” is only a small percentage of what exists. 95% to 97% is “dark” to us. We says its invisible.

This is why I prefer to think of the Divine as “the Great Mystery.” I fall into human, anthromorphic descriptions of that Mystery too, as God, or God X or any of the ten thousand names by which that Mystery has been and is proclaimed by many. Male/Female, you name it, I sense that all that is is beyond what can be named, hence my use of the word Mystery .

As I told my students at the Graduate Theological Union, it’s critical to remember that Christ was not a Christian, nor was the Buddha a Buddhist. The religious traditions that sprung up after the lives of Christ and Gautama Buddha, for example, the two I’ve studied the most, were started by their followers well after their deaths. As far as I can tell, Christ and the Buddha came to love and be of service. They didn’t found institutions. They illuminated the human capacity for love, compassion, understanding, wisdom and service. They were activists even in their silence, in their retreat from the world, in their stillness, in the ways in which they nourished themselves even without food.

China Galland

Thinking about Love

30 November 2016

The experience of cleaning the graves at Love Cemetery is a profound one. Maintaining this 175-year old African American cemetery with the local community is a deep meditation on life, death, and the soul of American identity. I will never forget it. One becomes newly aware of the generations upon generations that have been lost and remained unseen. In paying tribute to Love Cemetery and its survival, I had the overwhelming sense that there may be no more necessary and immediate work than searching for a way to honor those upon whose backs this country was built, people who were once enslaved. What is all the more profound is that in this act of honoring the past we may be touching upon an unexplored source of healing for our present time.

Going to Love Cemetery inspired me. Our theater company in Oakland, CA, The Ubuntu Theater Project, does site specific theater productions in found spaces. Part of our mission is to enliven spaces that have been forgotten by the community and to reveal the latent vitality therein. There is perhaps no space more important and more in need of re-vitalization and care than Love Cemetery.

Going to Love Cemetery inspired me. Our theater company in Oakland, CA, The Ubuntu Theater Project, does site specific theater productions in found spaces. Part of our mission is to enliven spaces that have been forgotten by the community and to reveal the latent vitality therein. There is perhaps no space more important and more in need of re-vitalization and care than Love Cemetery.

The word Ubuntu comes from a Zulu proverb and means, “I am because we are” and “I am a person through other people. My humanity is tied to yours.” Our theater is made up of a collection of artists who are committed to creating compelling works that unearth the human condition and unite diverse audiences through revelatory work.

Three of us hope to come and help create a week-long intensive workshop with whole community, including the four universities whose students and faculty are helping at Love too. The workshop would include cleaning Love Cemetery and creating and performing a ceremony of honesty and intent – in which we might plant the seeds of hope for racial reconciliation in our country. If people are so moved. Truth, ragged as it may be, must be given its due; only then can reconciliation emerge. An offering.

Our purpose is two-fold. First, it would allow new people to enter Love Cemetery and experience what those who have intensely labored on Love know to be true—that the preservation of these cemeteries is essential to our cultural memory and healing.

In our workshop, this knowing would be expressed through song, recitation, movement or dance, poetry, ritual, prayer, even silence. We would co-create whatever emerges, be it a ceremony of celebration or a rite of mourning and loss. Secondly, throughout this week-long workshop participants – whether they are descendants, students, faculty, community member or volunteer, would have the opportunity to meld local history, education, creativity, and agency into a piece of their own creation that reverberates with personal and public significance.

In our workshop, this knowing would be expressed through song, recitation, movement or dance, poetry, ritual, prayer, even silence. We would co-create whatever emerges, be it a ceremony of celebration or a rite of mourning and loss. Secondly, throughout this week-long workshop participants – whether they are descendants, students, faculty, community member or volunteer, would have the opportunity to meld local history, education, creativity, and agency into a piece of their own creation that reverberates with personal and public significance.

Finally, the underlying theory of this project is that in order for us to heal as a society we must discover and work to reveal the invisible ways in which we are intrinsically bound. All the arts have this potential, theater especially. This Zulu proverb which we’ve taken as our name – Ubuntu – reminds us constantly of our invisible connection. Theater has the capacity to create an experience that excavates this essence of our being: that we are all intrinsically bound, not only to one another in our present time, but to our ancestors of ages past and the generations to come. If we do not take the time to value and seek new ways in which to honor our cultural history, we prohibit the possibility of healing for ourselves and we prevent it for the children of the future.

Love Cemetery is in many ways the epicenter of these past, present and future threads. If we can weave them together through Love, we offer ourselves an inspiring and very real possibility of hope. Most importantly, we offer our children and our children’s children the future.

Michael Moran, MFA

Ubuntu Theater Project

Co-Artistic Director

http://www.ubuntutheaterproject.com/

Felicia Furman’s newest post on “BitterSweet, Linked Through Slavery,” is superb, important, and nuanced, like her excellent documentary film, “Shared Histories.” Go to her website http://www.sharedhistory.org and buy the DVD “Shared Histories” and support Felicia’s work to fund scholarships for descendants. Felicia’s work as a white person who’s family once enslaved people is an inspiration for any and all who care about healing and reconciliation not only in the United States but everywhere.

“No history is mute. No matter how much they own it, break it, and lie about it, human history refuses to shut its mouth. Despite deafness and ignorance, the time that was continues to tick inside the time that is.”– Eduardo Galeano

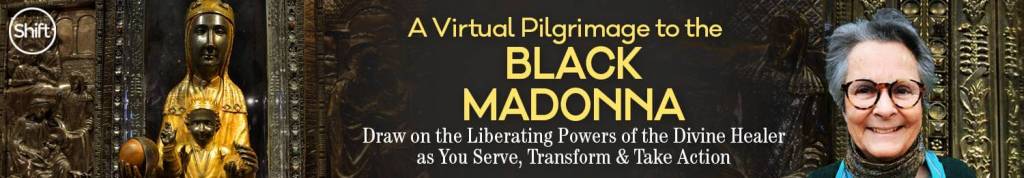

Archie Rison, one of our new volunteers, drove 400 miles round trip from outside of Dallas with his friend Obadiah Johnson, to help. It was one of the few cleanups that I’ve missed in many years. My cousins Philip and Sharon Verhalen were there with some of the Boy Scouts. Though Philip is the Scout Master, the Scouts who come do it strictly as volunteers. No merit badge. Over a dozen students from nearby Wiley College came, as well as a handful of students from East Texas Baptist University. ETBU faculty member, Dr. Sandy Hoover, chair of their history department, joined in again too. Members of the Marshall community, including one of Scout’s mothers came too. Without the vigilance and hard work of the Love Cemetery Burial Association, especially the President Doris Vittatoe, nothing can happen at Love, but that’s another story for another time. The behind the scenes work of organizing cleanups, sending in certified mail notices, and so forth goes on all year. Richard Johnson, Doris Vittatoe’s brother, moved back to Marshall a few years ago and has been a stalwart helper ever since. Archie wrote to tell me how it went: “I am so passionate about preserving the graves of my own ancestors that I regard helping at Love Cemetery as a part of my journey to show my appreciation. Though I’m not related to anyone buried at Love, I feel an attachment to these brave souls. They lived in a time when hope was a complicated task tied up with just staying alive. The least I can do is show up and help. Maybe this will influence others to do the same. Though I drove 400 miles round trip, I would drive even further for such a cause. “I was especially impressed by the students from Wiley College who turned out to help, there were a least a dozen of them. Remember NaQuita Elmore?” he asked. “She was with us last April when we came out to Love with Ysaye Barnwell (insert link? To video?). “NaQuita was the one who walked over a mile to find the cemetery last April. She led a handful of other Wiley students who hadn’t been there before either. She was just so determined to find us! They were all members of Wiley’s choir. They started singing while they walked and it turned out to be such a great experience that this past Saturday, she suggested that they walk again, and started up singing. “Once they got to the cemetery and started clearing the graves, they just kept right on singing. It was something! It was like being at a choir recital except it was outside we were all working together. It also reminded me of what I’ve heard and read about how people in slavery kept singing all day long, continuously, while they were out working the fields.”

4-5-14, Wiley College students left to right: NaQuita Elmore, Marcus Shelton, Kylan Pew, Cameron Spearman, and Starsha, on either side of Ohio Taylor’s headstone. Taylor was born in 1834 and died in 1918. He is Mrs. Doris Vittatoe’s great-grandfather. Vittatoe is the President of The Love Cemetery Burial Association. Photo by Archie Rison

Dr. Felton Earls’ research at the Harvard School of Public Health on

The Most Important Influence In a Neighborhood

Ten years ago The New York Times ran a story I never forgot, a story that confirmed my sense that Love Cemetery mattered in ways that we hadn’t thought of, and that it matters to a larger community than we had yet realized. I cut out the story about Dr. Felton Earls, then at Harvard’s School of Public Health, and his extraordinary research project in criminology. Dr. Earls is now Professor Emeritus at Harvard Medical School. Felton Earls ought to be a household name.

By 2004, when Dan Hurley’s feature on Dr. Earls came out in the Times, Earls had already spent a decade running one of the longest, most expensive, and well-researched studies of criminology to date. Backed by ten years and over $51 million of research, Dr. Earls, concluded that the most important influence in a neighborhood …. is a neighbor’s willingness to act on behalf of the benefit of another’s need, “particularly for the benefit of another’s children.”

Though his research was on the development of criminal behaviour, Dr. Earls noted that his background is public health, that his concern was ultimately on discerning and documenting what makes a community work. What makes the difference? Why does one lot in a community get transformed into a communal garden, while another becomes a breeding place for rats?

What Dr. Earls and his researchers documented over the years, painstakingly, on video, was that the deciding factor is the neighbor — your neighbor, my neighbor – the neighbor who is willing to act on behalf of someone else, especially on behalf of someone else’s child.

In the full article (not what came up in the Times Archives this morning), Earls talked about the effect of the willing neighbor, about how equally strong an influence the individual is, as strong as a genetic influence or economics He used the term “robust” to describe the neighbor’s effect.

“It’s all about taking action, about making an effort,” Dr. Earls said as though to say there’s no magic, there’s only effort and taking action, robust effort.

Thank you for following our effort, our action. Every post you read, every message you forward, post, and circulate maximizes ours — Resurrecting Love!

Here’s the 2004 article on Dr. Earls by Dan Hurley, from The New York Times Archives: “SCIENTIST AT WORK — Felton Earls, On Crime As Science (A Neighbor At a Time)” By DAN HURLEY Published: January 6, 2004

”That couldn’t be more perfect,” said Dr. Earls, a 61-year-old professor of human behavior and development at the Harvard School of Public Health. Gazing at a homemade sign for the garden at the corner of East Brookline Street and Harrison Avenue, he pointed out four little words: ”Please respect our efforts.”

”We’ve been besieged to better explain our findings,” he said. For over 10 years, Dr. Earls has run one of the largest, longest and most expensive studies in the history of criminology. ”We always say, It’s all about taking action, making an effort.”

Dr. Earls and his colleagues argue that the most important influence on a neighborhood’s crime rate is neighbors’ willingness to act, when needed, for one another’s benefit, and particularly for the benefit of one another’s children. And they present compelling evidence to back up their argument.

Will a group of local teenagers hanging out on the corner be allowed to intimidate passers-by, or will they be dispersed and their parents called? Will a vacant lot become a breeding ground for rats and drug dealers, or will it be transformed into a community garden?

Such decisions, Dr. Earls has shown, exert a power over a neighborhood’s crime rate strong enough to overcome the far better known influences of race, income, family and individual temperament.

”It is far and away the most important research insight in the last decade,” said Jeremy Travis, director of the National Institute of Justice from 1994 to 2000. ”I think it will shape policy for the next generation.”

Francis T. Cullen, immediate past president of the American Society of Criminology, said of Dr. Earls’s research, ”It is perhaps the most important research undertaking ever embarked upon in the study of the development of criminal behavior.”

The National Institute of Justice has so far spent over $18 million on Dr. Earls’s study — more than it has ever financed for any other project. The MacArthur Foundation has spent another $23.6 million on the study, likewise the most it has spent, and money from other government agencies has brought the cost of the project to over $51 million so far.

Dr. Earls came to his current work by a circuitous route that included one great leap. Born to working-class parents in New Orleans, he graduated from Howard University’s College of Medicine and pursued a postdoctoral fellowship in neurophysiology at the University of Wisconsin.

It was there that he met Dr. Mary Carlson, a neurophysiologist. They have been married for 31 years and are now collaborating on a project in Tanzania to promote the well-being of children who have lost their parents to AIDS.

When they met, they were both aiming for a white-jacket career in the laboratory. In fact, back in April 1968, Dr. Earls spent 36 hours straight, alone for much of the time, in a soundproof room, mapping the responses of a cat’s brain to various high- or low-frequency sounds.

When he emerged from his laboratory on the evening of April 5, the Wisconsin campus was in an uproar. Only then did he learn that Martin Luther King Jr. had been killed the day before. Having participated in rallies led by Dr. King, Dr. Earls says he reacted instantly.

”I realized that I couldn’t have a career in neurophysiology. I couldn’t remain in a laboratory,” he said. ”King’s death made me see that I had to work for society. My laboratory had to be the community, and I had to work with children because they represent our best hope.”

Six months later, he left Wisconsin and went to East Harlem to train as a pediatrician, then to Massachusetts General Hospital to train as a child psychiatrist, and finally to the London School of Hygiene for a degree in public health.

His research is, in essence, about the health of communities, not just about crime. ”I am concerned about crime,” he said, ”but my background is in public health. We look at kids growing up in neighborhoods across a much wider range than just crime: drug use, school performance, birth weights, asthma, sexual behavior.”

His study, based in Chicago, has challenged an immensely popular competing theory about the roots of crime. ”Broken windows,” as it is known, holds that physical and social disorder in a neighborhood lead to increased crime, that if one broken window or aggressive squeegee man is allowed to remain in a neighborhood, bigger acts of disorderly behavior will follow.

This theory has been one of the most important in criminology. It was first proposed in an article published 20 years ago in The Atlantic Monthly, written by Dr. James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling. The theory provided the intellectual foundation for a crackdown on ”quality of life” crimes in New York City under Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani.

Today, ”broken windows” policing is endorsed by police chiefs across the country, its proponents sought out for lectures and consulting around the world. But from the beginning, Dr. Wilson concedes, the theory lacked substantive scientific evidence that it worked.”